Haxted Thinking No. 04 / December 2020

Haxted Thinking is a monthly newsletter for anyone interested in how buildings are designed, made and used.

Edition No. 4: December 2020

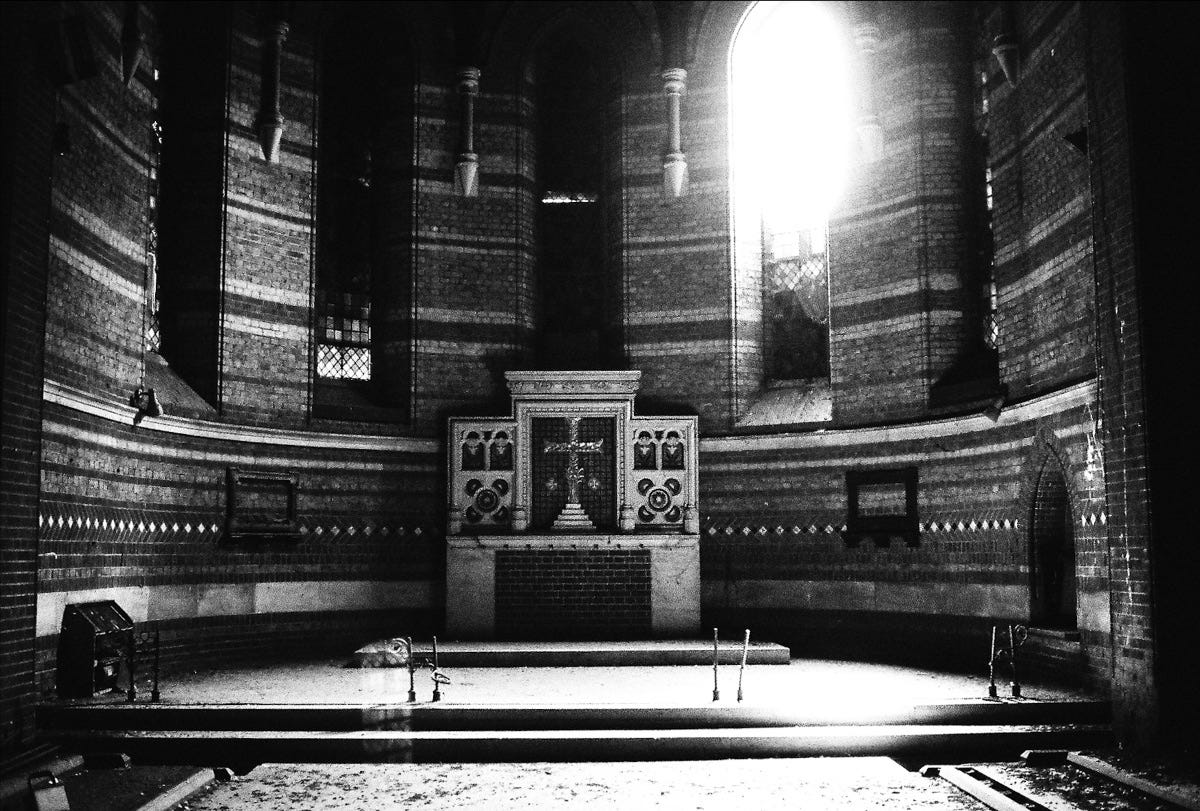

“Forget your perfect offering. There is a crack, a crack in everything. That's how the light gets in.” 1

Leonard Cohen

2020 and onwards to 2021...

So here we are at the tail end of an extraordinary year. It’s tested us all in ways we could never have imagined. As I write this, news of the mutated strain of Covid-19 has just been released and Christmas plans for many will have to change. Our hopes for something approaching a return to normality now rest on the roll-out of the Pfizer vaccine and the soon to be approved Oxford/Astra Zeneca vaccine. 2020 has been characterised by intense levels of tragedy around the world. Our thoughts at Haxted are with everyone who has suffered loss as a result of the pandemic.

I remember Michael Jordan saying that talent may win games but that teams win championships. And he’d know. This year Haxted has been stress tested to it's very core. And we’ve survived thanks to the talent of some very dedicated people. I’d like to sincerely thank Steve Durant, our Operations Director, in particular. Without any hesitation Steve jumped both feet into the deepest of trenches when the pandemic changed everything. Leadership by example. Real leaders ask to be tested in the most trying circumstances. They make sacrifices for the benefit of others. And they are imperfect, like everyone else. But the difference with great leaders is they don't allow that imperfection to stop them taking fully committed and bold action. They feel all the fear and do it anyway. They forge strength into a team like a blacksmith does into a precision knife blade. They are invaluable. Leadership will be needed more than ever as we move into 2021. There will be cracks. But that's good. That's how the light gets in.

There is a privilege and a responsibility that comes with building. I wrote about this in newsletter 2. At Haxted our culture is predicated on meeting the challenge of producing well-designed, beautifully executed buildings, head on. It's not easy but it is necessary. The thing is, architecture and the buildings we make, affect the lives of very many people. Not just those that use them, or live in them, but anyone who interacts with them, anyone who sees them. This is why architecture is the most democratic of arts. You don’t get to choose to experience it. President Obama understood this when he gave the Pritzker Prize speech in 2011and said of architecture:

“It is about creating buildings and spaces that inspire us, that help us do our jobs, that bring us together, and that become, at their best, works of art that we can move through and live in. And in the end, that is why architecture can be considered the most democratic of art forms.”

In a post Covid world we need this understanding maybe more than ever. It’s a fact that the property sector often puts profit before this purpose. It puts money before magic. Investor returns before user’s wellbeing. It doesn’t see the creation of new spaces as an art process. At Haxted we are trying to make spaces that are are imbued with artful thought. Obviously as a business we need to be profitable to survive so this isn’t art at all costs. But I’ve always tried to see profit as the consequence of being creative, building well and delighting our customers. As we head into 2021 we are re-doubling our efforts in this regard. And that starts with putting wellbeing and creativity at the heart of everything we do.

Wellbeing and creativity

The design of our built environment has deep rooted implications for our quality of life. On average, we spend nearly 21 hours a day indoors. That’s 21 hours a day inside buildings. Almost 90% of our time, whether it be working, relaxing, learning, playing or just living out life, is spent in an indoor space. So it is vital that our living and working spaces are designed and built to maximise well-being.

If we were in any doubt about this before, the Covid-19 pandemic has shattered those doubts. The transition from traditional patterns of work to a working from home culture has heightened the focus on how we want to live and work, to a massive degree. The stark advantage of a home that is intelligently designed, flexible and adaptable has been illustrated to full effect during 2020.

In the post pandemic world, the demand for spaces that maximise well-being will be unremitting. Well-being can be defined as the state of being healthy, comfortable and happy.2 This triple bottom line of well-being has a direct parallel with the Vitruvian ideal of ‘fimitas, utilitas, venustas’ that I wrote about in . If ‘firmitas’ (firmness or solidity) is health, ‘utilitas’ (commodity or usefulness) is comfort, and ‘venustas’ (delight or beauty) is happiness. So you could say Vitruvius laid down a blueprint not just for good architecture, but more importantly for how to make spaces that promote well-being above all else.

Homes and workspaces that promote well-being are responsive to their users’ needs and behaviours. They are resilient and adaptive in the face of shocks. They are inherently elastic. And we need them more than ever as we transition to a world beyond Covid – a world that inevitably includes a new form of hybrid living and working.

When spaces maximise well-being, they also maximise creativity. And spaces that maximise creativity are spaces that free up how we live, work and play. In essence creativity is the process of recognizing ideas, alternatives and possibilities and transforming them into something valuable. Creativity is the fusion of intelligence and imagination. It is the vitally important ingredient for a meaningful and fulfilled life. World renowned psychologist, Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi, puts it like this:

“Of all human activities, creativity comes closest to providing the fulfillment we all hope to get in our lives. Call it full-blast living. Creativity is a central source of meaning in our lives. Most of the things that are interesting, important, and human are the result of creativity. What makes us different from apes—our language, values, artistic expression, scientific understanding, and technology—is the result of individual ingenuity that was recognized, rewarded, and transmitted through learning. When we're creative, we feel we are living more fully than during the rest of life.” 3

Spaces that lack creativity and fail to stimulate creativity, diminish us. They have no spark, they don’t excite us. They don’t delight us. They fail on the third leg of the Vitruvian triple bottom line. And then they become quietly overwhelming. So real estate desperately needs creativity. The homes and workspaces we make must facilitate and enhance the creative drive in the lives of those that use them. And creative spaces are more exciting, and they are more soulful. These are the spaces we need most of all.

It’s been said that a business strategy is nothing more complicated than finding something really difficult to do, and doing it better than all of the competition. If that’s the case then Haxted’s strategy is to make spaces that enhance wellbeing and creativity for their owners and users, better than everyone else. Spaces that promote “full blast-living.” In 2021 and beyond, these are the spaces you will know us by. And there'll be more to come on how we may be able to help with your own project.

Brutalism

Last month I mentioned brutalism. It's an architectural style that’s always fascinated me. Maybe this was inevitable given that I arrived on this grand stage in 1968, the son of an Italian émigré father (himself born in 1928 in Naples under the fascist rule of Benito Mussolini) and grew up in the London Borough of Croydon, an urban landscape replete with massive concrete flyovers, underpasses and point and slab tower blocks.

This fascination intensified in my University days at Reading where I studied in the iconic FURS building (designed by Howell, Killick, Partridge and Amis and built 1970-72) which was Listed Grade II by Historic England in 2016.

Interest in brutalism seems to have exploded in the last few years. Perhaps this is because some of the most iconic brutalist buildings in the UK have recently been re-invigorated. See Lynn and Smith's Park Hill in Sheffield, and Goldfinger’s Balfron Tower in the East End. And especially the sublime Preston Bus Garage where John Puttick has produced a brilliant refurbishment after the building narrowly avoided the wrecking ball. Or perhaps it’s because many of the UK’s most iconic brutalist buildings didn’t dodge demolition – Alison and Peter Smythson’s Robin Hood Gardens in Poplar, Rodney Gordon and Owen Luder’s Tricorn Centre in Portsmouth and Trident Car Park in Gateshead, and John Madin’s Birmingham Central Library are all gone.

But I think the reason for renewed interest in brutalism is due to an emerging cohort of people who recognise the simplicity and honesty of brutalist architecture. And see it as a metaphor for a less complex, and less fussy, material driven, way of living. Strangely enough I am writing this newsletter from a desk designed by John Madin, and salvaged from the Birmingham Central Library demolition. It wears its history clearly.

Brutalism, as a movement, came to prominence in 1952 with the completion of Le Corbusier’s Cité Radieuse in Marseilles, better known as Unité d’Habitation. Flourishing during the post-war period of European civic rebuilding, brutalism had its roots in the powerful, muscular bunkers, shelters and military paraphernalia of Friedrich Tams’ Nazi constructions. So I suppose unsurprisingly, like architectural marmite, it seems to divide opinion along straight love it or hate it lines. And yet it was only around for a relatively short period of time. In all but the Soviet east, it had largely disappeared as a design movement by the late 1970’s.

Brutalism’s problems started with its etymology. The OED has two meanings for it, and the non architectural one is ‘cruelty and savageness.’ And this has led to a common misconception. Brutalist architecture was not so named because of its totalitarian origins, nor its apparent forcefulness and aggression, but rather prosaically, from the descriptive phrase used by Le Corbusier to describe the unadorned finish of his masterpiece at Unité - ‘béton brut’ - meaning raw concrete. In 1955 the architecture critic Peter Reyner-Banham declared the emerging movement of raw concrete architecture the ‘new brutalism.’ 4

The truth is brutalist architecture was never meant to be easy. And there is no reason why we should instinctively feel comfortable with it. We come from a culture that historically values the quaint, the pretty, the accessible, and the easily digestible, above all else in its architecture. Brutalism, a response to the utopian search for a vision of what post-war Britain could be, was anything but that. Heroic, bold, commanding, and free of design fripperies, brutalist buildings were about honesty. This was an architecture of uncoated concrete exteriors, massive frames and (sometimes crudely) textured surfaces. This was architecture that eschewed frivolity. It was affordable in austere times.

Anyway in the hands of a masterful few, the drawing pen of brutalism was wielded with extraordinary results. The buildings that we got were uncompromising, ambitious hulks imbued with complexity, character and intelligence – the very antithesis of the mainly lightweight, insipid dross that passes for civic architecture today. What brutalism lacked in elaboration, decoration or colour, it more than made up for in form, shape and textural quality. Concrete, the material of brutalism, had its greatest heyday since the masterful builders of the Roman empire completed the Pantheon 2000 years earlier.

The story of brutalism is inextricably linked to the magic of concrete. Cook lime at 1480°C, crush to powder, add to sand and aggregate, mix with water, leave to harden. Result concrete. 7.5 billion cubic metres of the stuff are used every year around the world. That’s 1 cubic metre for every man, woman and child on earth. It is the most ubiquitous of building materials, always present, mostly unnoticed, a perfect canvas for architect, engineer and artist. Concrete: austere, bleak, cold, hostile, utilitarian; but also durable, reliable, efficacious, lively and warm. It is materiality made visible, with its evident craftsman’s marks, shutter patterns, and its endless textural variants. What you see is what you get. No nonsense.

Brutalism’s history here in the UK has been complex. In 2003, just five years before his death, Rodney Gordon told fellow architect David Adjaye, as they stood on the top deck of the Tricorn Centre before its impending demolition: “Any piece of architecture worth being called architecture is usually both hated and loved.” Brutalism is not beautiful architecture, it is beyond that. If the sublime, as Edmund Burke put it, goes beyond beauty, because like the great mountains and oceans it has the power to compel and destroy us, then brutalism has it. In spades. Not for nothing is it the architecture of choice for the dystopian vision of A Clockwork Orange and Get Carter.

In his mischievous and compelling BBC documentary “Bunkers, Brutalism and Bloody-mindedness” Jonathan Meades (who lives in Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation) says that whilst brutalist buildings never asked for our love, they do deserve our respect. Something that they have had precious little of in the recent past. “There was good brutalism and bad,” says Meades, “but even the bad was done in earnest.” It is that alone, if nothing else, that sets brutalism apart from the stylistic mess that we all too often have to tolerate in our present day metropolitan civic architecture. Perhaps the tide is turning now as a new generation looks for a connection back to a less complicated way of life.

Finds from this month’s dig

It's probably too late for Christmas gift recommendations but here’s a few things I’ve enjoyed immensely during the last month’s dig. All of them have contributed in some way to my invigorated quest for “full blast living.” Have a safe and peaceful Christmas everyone. Please drop me an email if there’s anything we can do to help.

Music:

The album is out. You knew I’d recommend it. Idiot Prayer, Nick Cave Alone at Alexandra Palace. It's wonderful. Sounds absolutely mustard on the Linn. I urge you to try vinyl if you haven't before. I wrote about it back in 2013 for the Hiut Denim yearbook. And I talked about it with the brilliant melancholic Luke Sital-Singh on my podcast back in 2018.

I’ve been getting more and more into Leonard Cohen lately. You have to. No-one in contemporary music understood the human condition better. No-one else was better able to evoke the dance between the darkness and light, between sorrow and joy. He’s all in yin-yang. I adore his final album You Want it Darker (2016) released sixteen days before his death. The press conference was amazing. Lately I’ve also been enjoying Songs of Love and Hate (1971) very much.

Books:

Rory Sutherland is the Vice Chairman at Ogilvy. His new book Alchemy is truly brilliant. He’s from the same common sense mould as Dave Trott (brilliant blog and who’s 4 books are highly recommended). Quite honestly most of what's written about brand and marketing is awful dirge. These two are the exceptions. Titans.

Scott Galloway’s book Post Corona is very US focused but is excellent on what to expect in 2021. It acts as a companion to his 2020 podcast series The Prof G Show.

I came upon Learning from the Octopus by Rafe Sagarin looking for books about adaptation and complex systems. It's full of practical stuff about how adaptation and resilience can support new distributed forms of leadership. To that end it had echoes of the more recent Team of Teams by General Stanley McChrystal which I read a few years ago and found fascinating. You'd be amazed at what the biologically super adapted octopus can do.

American scientist E O Wilson is fast becoming my new favourite person. What a brilliant man. A world leading biologist and a most compelling writer on science, he’s 91 now. I’ve come to him unforgiveably late. His The Origins of Creativity is wonderful. It links well to Matt Ridley's also excellent new book How Innovation Works.

Film:

I’ve been working with the fabulously talented young director and filmmaker Jay Brasier-Creagh on a number of new projects this year. The Isolation Series, which Haxted supported, is a really beautiful, evocative piece of work. We’ll be doing more with it during 2021 so stay tuned for that.

Jay’s latest piece of work “A Handful of Dust” documenting The Fireflies Patagonia ride was released last week. Fireflies is a cycling charity that supports blood cancer research https://thefirefliestour.com.

Jay also put me onto Mubi (actually he insisted I started watching film as part of his tuition in filmmaking which we embarked upon early in lockdown 1). I thoroughly enjoyed two drama films (both sub-titled) this month:

On Body And Soul, Ildikó Enyedi, Hungary, 2017

A Short Film About Killing, Krzystof Kieslowski, Poland, 1988

I’ve also re-watched two peerless documentaries, the first about Charles and Ray Eames: Eames: The Architect And The Painter, Jersey and Cohn, US, 2011; the second an utterly beguiling and gorgeously told story about Japan’s most celebrated Sushi restaurateur - Jiro Ono - and his 3* restaurant Sukiyabashi Jiro: Jiro Dreams Of Sushi, David Gelb, US, 2011

I also watched an eclectic four part series of short films about John Berger: The Seasons in Quincy: Four Portraits of John Berger, Dziadosz, MacCabe, Roth, Swinton, UK, 2016. There is no better way to make apple pie than to watch this while you do so. Do also read Berger's brilliant art criticism book Ways of Seeing, and the original 1970's series is still available on YouTube if you fancy it.

TV:

I was late to the Chernobyl party. Oh my. What a brilliant piece of drama documentary. The cinematography is peerless and the acting excellent.

I’ve also just finished the The Queen’s Gambit on Netflix. My chess is as useful as a chocolate teapot but I loved this. Here's the trailer.

A happy Christmas to all of you. See you on the other side.

(c) Jim Marsden 2019

Footnotes:

1 Leonard Cohen - Anthem from the 1971 album The Future

2 Oxford English Dictionary

3 Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Pyschology Today, 01/07/1996

4 The term ‘nybrutalism’ was architect Hans Asplund’s earlier playful description of a small house in Uppsala, in his native Sweden, designed in 1949 by his contemporaries Bengt Edman and Lennart Holm. Reyner Banham used this historical reference and expanded it by reference to Le Corbusier’s béton brut, into a bilingual pun, sensing mischievously, that the British arts elite would inevitably react with general horror to a civic architecture, both free of adornment and that sought to celebrate the rawness of unfinished concrete. He was right.

Who is Haxted?

Haxted is a real estate development company passionate about creating beautiful homes and workspaces at a fair price. Our business is grounded in the visceral belief that well-designed and crafted buildings can massively enhance the quality of peoples’ lives. Haxted came into existence during the 2008 global financial crisis, a time of great turmoil. Our thinking was that property needed less business-as-usual and more imagination. Less stuff and more soul. A little less conversation, a whole lot more action. It felt like the tectonic plates of how to do development were shifting. We needed to be nimble and ready to change shape at short notice.

The next few years are going to test us all. The decisions that we make about the buildings we choose to live and work in have never been more important. At Haxted we are fueled by curiosity and the art of the possible. If you’d like to see what we’re up to, or discuss doing something together please email me at cnavato@haxted.com. I’ll generally respond within 24 hours.